Creator of

Callanetics

Callan Pinckney

1939 – 2012

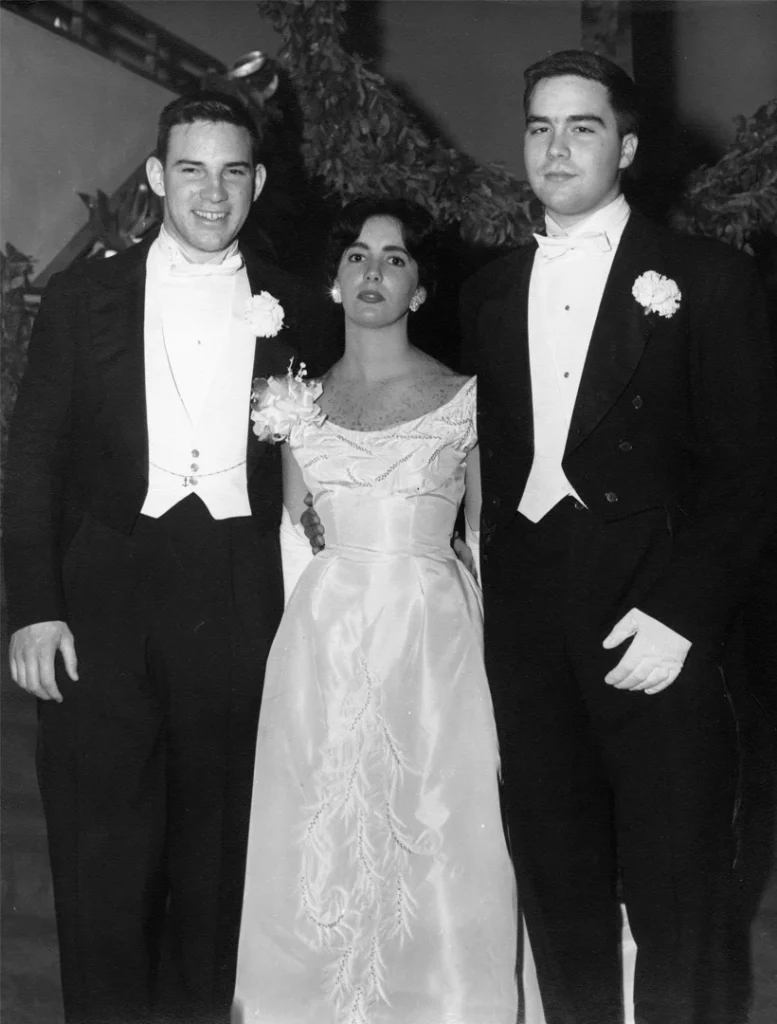

Born Barbara Biffinger Pfeiffer Pinckney, Callan was descended from the same Pinckney family that was instrumental in the founding of the United States, even helping to draft the Constitution.”

Growing up in and around Savannah, Georgia, Callan was taught to be a proper Southern Lady, with all the trimmings, rebelling all the way. “I was suspended by almost every school I attended,” she confessed. “I didn’t want to be there. I was busy dreaming of being in foreign lands. I wanted to experience life and people, not read about them in books. I couldn’t sit in a chair or at a desk for more than five minutes because of my back problems. Also, I had very bad dyslexia and they didn’t realize it in those days. So, I made the gamut of all the schools throughout the city. ”

Born with spinal curvatures (scoliosis and swayback), one hip higher than the other, and feet turned inward so severely that she wore leg braces to her waist for seven years of her childhood. “When I was an infant my mother massaged my legs for 3 hours a day. I was put in ballet classes, to try to turn my feet out even more. They didn’t realize that by turning the feet out, it was disaligning my backbone structure even more. So, I always had back problems.”

Callan went on to study classical ballet for twelve years with a protege of the legendary Michel Fokine. “I was able to excel at ballet which I loved. I trained with Ebba Olesen. She danced with Balanchine. I was also trained as a diver and a swimmer.”

Despite her aversion to academic ventures, Callan completed two years of college. The final straw was when she spotted her hosts at a fraternity party spying through a peephole into the ladies’ room. “If those boys were to be the future of our country, I didn’t want any part of them,” she recounted. “I sold my books and went back to Savannah.”

Callan worked as a clerk in a department store, saving every penny and plotting her “getaway.” This was a bit scandalous, considering her family’s background, but she was not thinking of appearances: The sales job paid more than anything else she could find, and money was what she was after, keeping expenses to a minimum, saving the balance for her travels.

Her father had adamantly prohibited her going abroad until she completed her college education. Callan was equally adamant about going. “My father’s telling me I couldn’t live three months without his support was the first major challenge in my life.”

Her Great Escape came when she threw her suitcase from a second-story window and climbed out after it, leaving her parents’ home behind. Friends drove her to the depot where she caught a bus for Wilmington, North Carolina. There she boarded a freighter bound for Germany.

The year was 1962. Armed with little more than her passport, Callan Pinckney was off to see the world.

Arriving in Bremerhaven, West Germany, the petite brunette had no particular itinerary, just an insatiable curiosity that led her through Europe for almost a year. In Germany, she acquired a Volkswagen from a friend . This was to become her home to cut expenses.

Without work permits, Callan took odd jobs to supplement her savings. Her first winter in London, she shovelled snow and coal for what amounted to $3.36 for an eight-hour day. There was no central heating and Callan was not accustomed to the frigid temperatures. She lived on biscuits and jam, cookies, and quantities of starchy foods to insulate her body in fat. Before long, she weighed 129 pounds- quite a jump for someone who is only an inch over five-feet tall and whose previous top weight had been 105.

Hearing about Africa from people she met in London, Callan explored the possibilities of going there. She was unable to get the necessary travel permits in England, so she hitchhiked to Hamburg and secured papers there, returning briefly to London to tie up loose ends and to purchase the rucksack that was to be her “mobile home” for the next eight or nine years.

For a while Callan worked in Capetown for an advertising agency by day and as a waitress by night. She talked her way into most of the jobs she held during her travels, determined to learn whatever skills were necessary once she secured the position.

Her soft, cultured Southern accent was foreign to Callan’s British and Afrikaans employers and co-workers. Consequently, she was asked to come to the office a half hour early every morning to be tutored in “proper English pronunciation.” “I was quite insulted. I told them I spoke modern English, not Elizabethan,” she laughs. Today, her accent is part American, part British, and all Callan. She is a verbal chameleon, reflecting the accents of those around her.

She spent almost a year in the bush of Central Africa. Part of this time she helped track animal migrations from place to place, leaving Zimbabwe, then Rhodesia, Zaire, then the Congo, and Kenya, when trouble began to brew.

Her survival instincts kept her body alive, but did not keep her fit and healthy. Her rapid weight gain in England had caused stretch marks on her hips. Her erratic, often inadequate, diet lead to malnutrition and three debilitating bouts of amoebic dysentery. (“I had diarrhoea for eight years.”) She dropped from a pudgy 129 to 78 pounds during the worst of these attacks. She was on Cyprus and had to be evacuated from the RAF Hospital there to make room for the wounded soldiers brought in from battle daily.

Callan further abused her body by doing menial labor to earn money and by carrying her backpack. Weighing almost as much as she did, it pulled her collar bones and strained her back and knees mercilessly.

For most of her odyssey, Callan lived among peasants, without any of the conveniences she had taken for granted all of her life. To this day she brushes her teeth without water. She usually wears a sweater or has one handy even in summer, remembering her fear of freezing for lack of clothing . “When I first returned to the States, I identified with the street people, the shopping bag ladies,” she confides. “I wanted to know what they carried in their bags, if the contents resembled what I had carried .”

In most of the countries where she lived or traveled , there was nothing written in English, not even signs on buildings. Callan tells that she had been living in New York for several years, following her travels abroad, wondering how people always knew the names of stores and streets. She had spent so much time in places where signs were unreadable that she had forgotten to look at them.

Callan maintained a detailed diary throughout her travels. As she left a country, she mailed a diary to her parents, making sure she could not be traced. “I never knew where I would be going next,” she explains. “I went where the roads and rides took me. I didn’t care where they went.” As for her diaries: “To this day I haven’t read them. I don’t think I ever shall.”

Much of this time she was alone, although sometimes she traveled with a Canadian girl whom she met early in her trip. Callan planned to hitchhike from Johannesburg to Japan.

She expected the trip to take about six months. It took seven years.

In Bombay, India, she was in an air raid. “I was walking down a street when a plane flew over and began shooting. I froze. Two men grabbed me and threw me into a doorway for cover. I hid my face in my arms and waited for the shoot- ing to stop. When I looked up, I saw a hand with only three fingers next to me. I was lying next to a leper. One of my greatest fears while traveling the world was contracting that disease.”

This prompted Callan to travel south to Ceylon. She and her Canadian companion, joined by an American girl who had been staying in the same place in Bombay, rode third class on the train to the border. Callan slept on luggage racks because the compartments, which had comfortable space for fifteen people, contained as many as sixty.

The trio missed the boat from India to Ceylon (now Sri Lanka) and had to wait a week for passage. To occupy their time, Callan introduced her American cohort to basic ballet. “That was the first time I noticed I could not do movements I had once been able to do so beautifully. I had no flexibility or extension . My muscles had no tone.”

She did not understand why it hurt whenever she sat. Her behind had fallen so much that it was now on her hips. Sit- ting on her sweater to cushion her tailbone had become second nature. Sleeping with a rag between her knees to keep them from rubbing together was a necessity.

Newspapers and current events were no longer a part of Callan’s life. Her day-to-day considerations were personal safety, drinkable water, clean food for survival , and finding a safe place to sleep.

Once Callan reached Japan, she recorded British voice- over tapes for advertising, wrote about her travels for a Japanese magazine, and modelled miniskirts. She also managed a bar and was responsible for hiring Western waitresses.

At that time, Callan was becoming increasingly aware of her body’s need for care. Back in London, she began to work seriously on her body. This was a slow, painful process for someone who had become so run-down. Doctors advised her to have surgery on her travel-damaged knees and cautioned that her back would never recover. “I looked terrible and was in constant pain . I thought that if I had to hurt all the time, I might as well look good. I had no other choice.”

When Callan returned to the United States, she appeared so emaciated and old that her mother fainted upon seeing her emerge from the plane.

Callan’s first job upon returning to the United States in 1972 was at a New York City exercise salon. “I left there because I didn’t approve of the way clients’ bodies were being treated. I was told to change the way I had been instructed to teach the exercises, supposedly so we could handle more clients in the salon. The owner of the franchise prohibited my asking the women I worked with if they had back problems, yet my back hurt when I did some of the exercises. Other people might have been hurting as well. This was extremely upsetting for me. The salon’s owner and I had studied this program from a woman who is a master in this field. I believed in my teacher’s program, and, in all fairness to her and to myself, I could not continue the way things were going.”

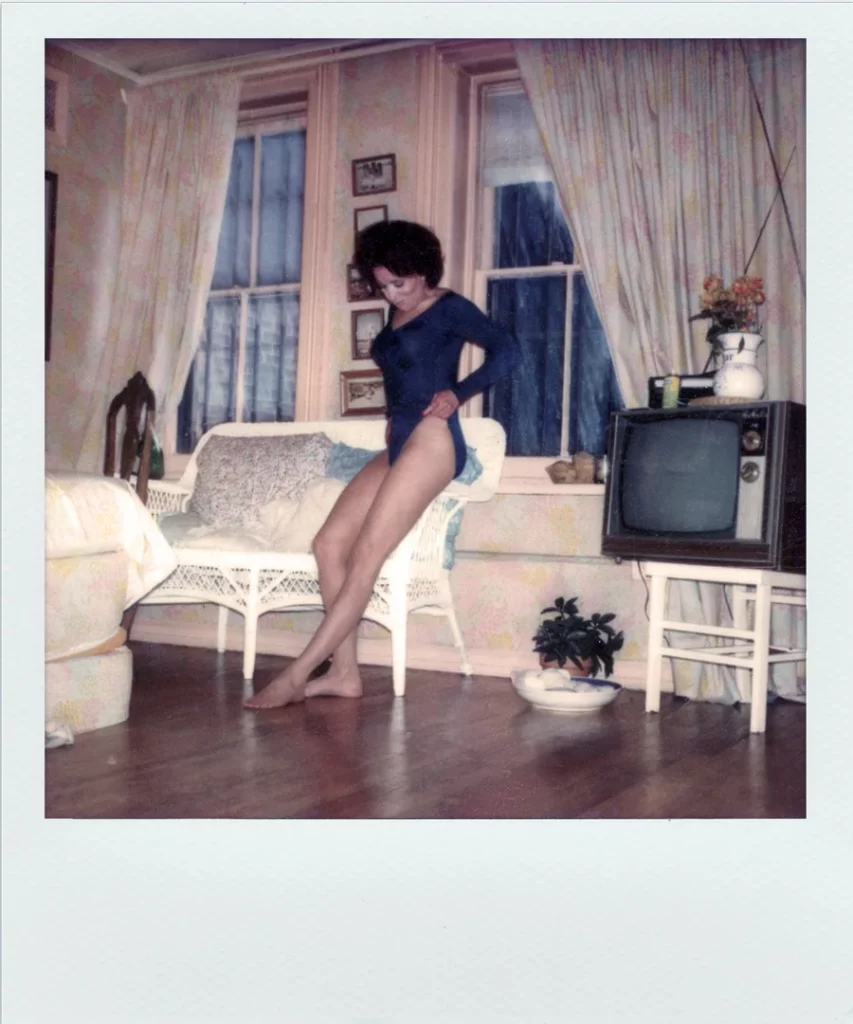

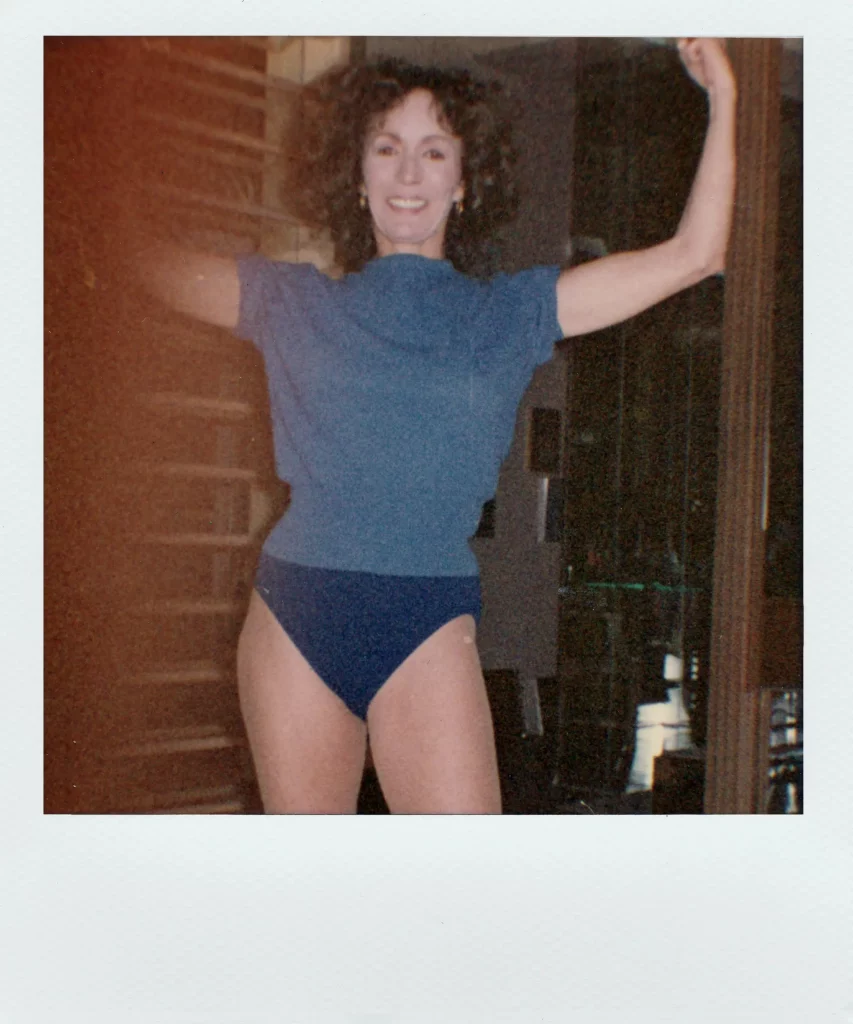

After leaving the salon, Callan experimented with other techniques, and the movements learned while studying ballet. “I found that if I felt back pain, I could simply shift my position as little as a fraction of an inch until my back no longer hurt. I got incredible results. I was determined not to do anything to start the back spasms again. I was amazed to see how strong and tight my body had become. My back had stopped hurting. I felt and looked as though I had been exercising for three hours a day for five years after only a few hours of these movements. I concluded that these deli- cate, precise movements are the key to successful exercising. I was so excited that I couldn’t wait to share the results with other people. I felt absolutely magnificent, as if I could spring like a majestic gazelle.”

When Callan began teaching on her own, she instructed students privately in their homes. ” I carried a metal pole with me from place to place to hang in doorways as a barre. We exercised on their living-room floors.” Soon, she offered classes in her own studio apartment.

“It was a circus. I had a barre across my closet door. Students looked at my pitiful wardrobe while they exercised. I rearranged it every week so they wouldn’t get bored at my interpretation of American clothes.”

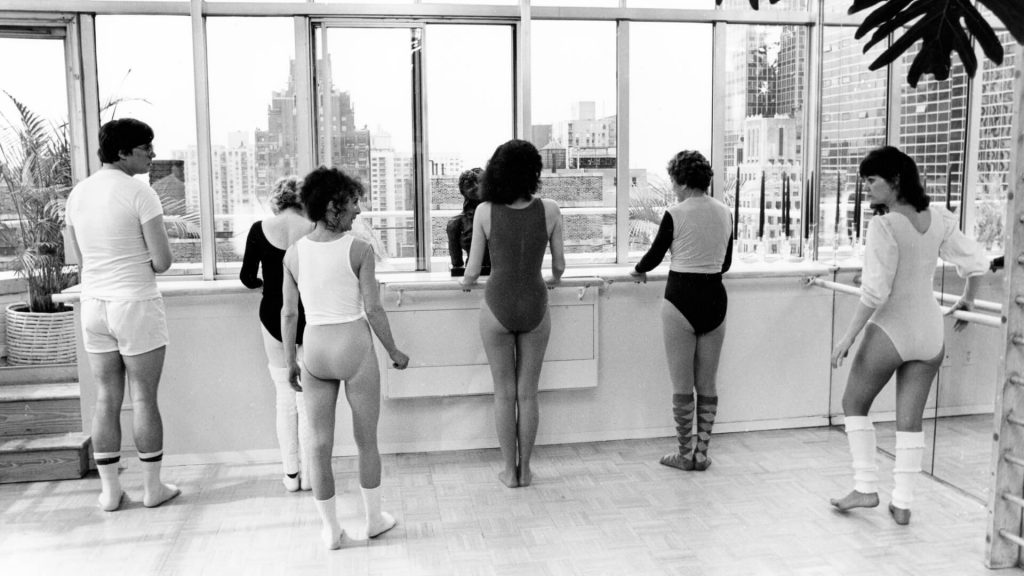

As her reputation grew, Callan moved to a penthouse overlooking New York’s East River. It gave her the space to create a proper studio from where she could teach “The Callan Reconstruction Method”, as she was now calling it. There was no pulsating music, no shrill cadence called by an instructor. There was no grotesque machinery to make the place look like a modern-day torture chamber. Students, men and women of all ages, sizes, and shapes, worked at their own speed under Callan’s careful scrutiny. She moved about the room, attending to each individual’s needs.

Callan’s classes were a far cry from the usual fitness center environment: indoor-outdoor carpeting; wall-to-wall people blinding in fluorescent lighting; overly chlorinated pools; and a sea of humanity, everyone doing the same things at the same time, whether or not their bodies are capable of it.

A new student observed, “Coming to Callan’s at seven o’clock in the morning is a terrific way to start the day. Someone wanders in at seven ten, someone else at seven twenty. Calian may be having breakfast or putting cream on her face, teaching while still in her nightgown. Despite this chaotic appearance, Callan has her hawkeye on everyone in the room. The way the mirrors are set up, she doesn’t miss a trick.

“The sun comes through the greenhouse glass and literally bathes the room in warm light, exposing every roll and bump in your body. You see exactly what you look like on the beach and it scares the daylights out of you.”

The natural light, reflected in the thirteen-foot mirrored walls, and the clear panorama of the city-the sky, rivers and skyscrapers-were magnificent inducements to exercise.

“One student told me that she had always thought her body was flawless…until she came here and saw it in bright light,” Callan laughed. “I believe people need this kind of objectivity so that they will be able to work on their bodies.”

There was always magnetic energy between Callan and her students. It was a powerful combination. Callan Pinckney was a one-of-a-kind woman.